I am a Recovering Self-Hating Asian:

How American Media Warped my Opinions on my Community

During Labor Day weekend, I saw “Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings” in theaters. Like many Asian Americans, remembering how big of an impact “Black Panther” had on the Black community, I was nervous about having high expectations as I entered the theater. I walked out with my expectations blown away. It was so jarring to see “Shang-Chi” represent such nuanced cultural aspects of Asian American life on the big screen, without being overly stereotypical or alienating to the non-Asian audience. In that moment, I felt so proud of being Asian American. Unfortunately, pride for my race was only something I’d began to feel in recent times, because the media I consumed growing up was a very different experience.

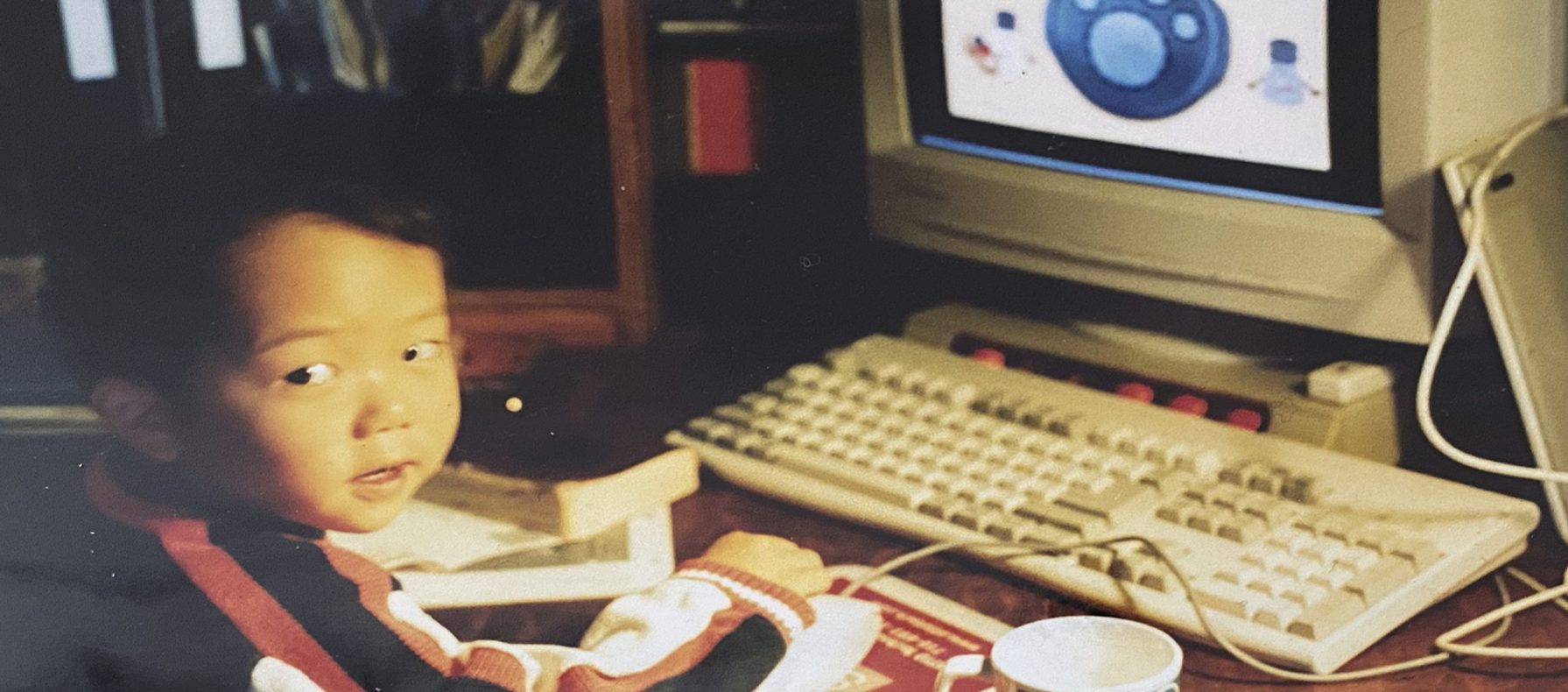

In the early 2000s when I was just a kid, mainstream media was still predominantly white-centric. The stereotypes of Asians being the nerds who can’t get a date were still widely strengthened by movies and TV shows. The main cast of high school teenagers would seldom have an Asian representative, and, at most, have a side character with a couple of one-liners that only perpetuated the stereotypes. Thinking back now, whether or not my peers had been influenced by the media, it had defined the perceptions I had of myself and my fellow Asians at large, without me even realizing it. I had always been easily influenced by media growing up; from growing my hair out like Anakin Skywalker to being obsessed with suits because of Barney Stinson. And with over a decade’s worth of media taken in, it’s not a surprise that what I considered life “should be like” became the white-dominant culture that was portrayed on the big screens.

Before I dive deeper, I want to preface by saying that my childhood was a good one. Many Asians have had to live through levels of racism that I’ve never even come close to experiencing. I wasn’t ever bullied outside of some mutual teasing amongst friends and I got along with most of my classmates. At worst, people would say my full name “Shane Shen Kuo” with a racist accent as a greeting. I would also receive perfect scores on the weekly math quiz, only to hear classmates dismiss my accomplishments by saying “Oh, Asian”. This reaction was common, despite my parents being artists that failed their math classes in college and are the furthest thing from tiger parents. These types of microaggressions were the extent of the racism I had to deal with. But microaggressions cut after a while.

I remember standing at a bus stop with classmates when one pointed out, “Your nose isn’t great, it’s too flat.” This led me to spend countless nights massaging, pinching, and pulling my nose in an attempt to sharpen, or “fix”, it. I remember a student trip to Barcelona where I and my non-Asian classmates sat around a lunch table eagerly sharing our knowledge on adult film actresses, but when my turn came to name one, I was skipped over. No one seemed to care or notice, so I decided to ignore it and continued to laugh along, but I’ll never forget the feeling. The feeling of realizing that, when it came to anything romantic or sexual, Asians didn’t belong.

Even if microaggressions hurt sometimes, to my teenage eyes, it was just “how things were” and it only made me assimilate more. Eventually, trying to not be the typical Asian stereotypes became a major driver for my personality:

“Asians are shy and not social” — I became a social butterfly.

“Asians are the ‘model minority’” — I became the rebel.

“Asians are pushovers” — I became the pusher.

In a lot of ways, I succeeded in doing what many Asian Americans are taught to do, which is assimilate into the dominant culture. But during my quarantine over the pandemic, I’ve had ample time to reflect on my childhood, and I’ve come to realize that it was BECAUSE I assimilated so well that I had become what many in the Asian community refer to as a “self-hating Asian”.

Since the 10th grade, I’ve repeated the same excuse when matchmaking friends attempted to pair me with Asian counterparts. “I am not attracted to Asian girls.” This line was something I would always say when the topic of relationships came up. The worst part was that I would say it with a sense of pride, as if me being an Asian and feeling this way would prove how worthy I am of fitting into white culture. Just thinking about it now makes me repulsed at myself. But at the time, I truly didn’t find Asians to be attractive. In my mind, it was like being Asian instantly put you below every other race when it came to looks. When people asked why, I would give reasonings like “they aren’t social enough for me to connect with them” or “they’re never inviting towards me”. All of which were just excuses because I hadn’t realized the truth about how I felt about my race. It wasn’t till the end of high school when I was dating an Asian girl, that I learned it wasn’t right of me to put all Asian girls into a box (and yes, aware of the meta-irony of this in retrospect). Even then, however, I didn’t consider why I felt the way I did originally.

Of course, I didn’t just feel this way about Asian women; I felt the same about Asian men, especially myself. I remember staring in the mirror every morning, thinking about how unattractive I was solely because I was Asian, internalizing that “this is the way it was” and that there was very little I could do about it.

The scariest part of being conditioned to think less of yourself just because of your race is that you’ll also feel the same towards others of your race as well.

I never wanted to admit it at the time, but because I felt I was unattractive simply for being Asian, I never felt any of my Asian guy friends were attractive either. I remember 6 of my Asian friends heading to a Bar Mitzvah, all in suits, walking down the street feeling like we were dashing young men taking over the town. For a moment, I had forgotten about how big the pond was, and when the pond was just us, I felt at ease with myself. But the second we walked into the party, I saw dozens of our non-Asian classmates all dressed up, dancing and chitchatting, and that feeling immediately went away. After that day, I continued to feel like we were all doomed to live an uphill battle when it came to finding love in America.

It wasn’t just the people that I had mentally pushed away; it was also the culture. I visited Taiwan every year with my family. While I was there, we would do all kinds of cultural activities with our extended family that lived there; gambling with dice on Lunar New Year in our chi pao, visiting temples to pray, and eating shark fin soup and stinky tofu. My mom used to drop me off at a bookstore in Taipei, and I would spend hours looking at all the manga there. I remember feeling so safe at the moment, not a single worry about what other Americans might think. But when I got back home to New York, I felt the need to hide those experiences from my friends. I would convince myself that I was above doing these “Asian” activities. I would tell stories to my cousins about all the crazy things we got up to in America. Parties that last to 3 am, late-night loitering on the streets; anything to show how cool us “Americans” were.

It’s clear to me now that it was less so to show how American I was, but more so to show how I was not like them; how I was not Asian.

Thinking back on it all now, I am truly filled with guilt and regret. I feel guilty for dismissing and undermining my people for so long; for thinking so lowly of them, as if me trying to run away from my roots made me superior. To automatically dismiss getting to know a girl romantically just because of her race. To hang with my closest Asian friends day after day, talking them up when deep inside I felt we were all the bottom of the barrel. I was no better than the racists screaming at us to “go back to our country”.

I regret not seeing how amazing all my cultural experiences were. Most of all, I regret not being able to feel proud of those experiences; to let them define me and have them be more than memories I hid in a box. Fortunately, after graduating college and separating myself from the student body, I’ve gotten the chance to feel more comfortable in my skin and find tons of ways to connect with my culture. I’ve incorporated many cultural aspects of day-to-day living that my parents do, such as making tea every day in a more traditional Asian manner or listening to music with Mandarin vocals. I am no longer afraid to wear Asian-inspired apparel. Over quarantine, I was moved to run a fundraiser for AAPI communities that were suffering during COVID by selling merchandise online to a niche video game community I’m a part of, which managed to raise over $6500 in two months. It took months of planning, ideating merchandise designs, and networking within the community before launch, and I had to do it all on my own within the confines of my apartment due to COVID. It took a lot out of me, but the amount of positive feedback and kind messages I got from fellow Asian Americans made me feel more included in our community more than ever before. The teenager I was would’ve never even considered putting any effort into supporting the AAPI community, let alone solo-run the campaign. Despite incredibly horrible circumstances, the state of the world gave me the chance to prove to myself that I have fundamentally changed from the self-hating Asian I had been to someone confident enough to love his roots despite what society has tried to make him believe.

So after “Shang-Chi”, I walked home thinking about how different my life would be if this movie came out when I was a kid. I would have felt the same pride in my culture I feel now, be able to walk into a classroom with my non-Asian peers having a better understanding of my culture after also seeing the blockbuster hit. Who knows, maybe my flat-nose-hating Caucasian friend would have dressed up as Shang-Chi for Halloween. Maybe his little brother will do it this year.

Movies like this make sure younger generations can feel comfortable in their own skin; by sharing and listening to authentic stories we can feel more represented and heard.

With society interacting online non-stop, the forms of media have evolved and become more accessible than ever before; so we need to make sure the content doesn’t repeat the same mistakes of the past. That’s why I felt the need to write about my story — so people can see the inner cultural identity struggle of an Asian man, something not nearly represented enough in media even today. I know mental health can be very taboo to discuss so openly in our community, but it’s the lack of discussion that keeps the flames of identity crises in our community alive. Our people came to this country for new opportunities, but what’s the point if we lose who we are in the process?

UI/UX Designer&

Illustrator&

ADMERASIA

Shanek@admerasia.com

Racism Is Contagious by ADMERASIA – a platform that provides consolidated, impactful tools to combat the spread of hate crimes against the Asian American community. Visit https://racismiscontagious.com/ to learn more.[R]EVOLUTION by ADMERASIA – a platform that connects brands with Asian American innovators and gamechangers rewriting the rules for social advocacy, content creation and entertainment. Visit www.admerasia.com/revolution to know more.